Clever endings are the cherry on top of well-written essay. And, as noted in my original post in this conclusion-writing series, there are several ways to coax them out of your students. This article focuses on two techniques that middle school writers can easily master: echoing the lead and word play.

Echo the Lead

I first introduce this strategy when teaching students to write a lead (a/k/a hook) for their introduction. It creates a sense of completion by mirroring the type of lead used in the first lines of an essay with those used in its final lines. It gives the reader the impression that they’ve come full circle.

If you’re familiar with my ABCs of Lead-Writing, you’ll recognize the list of essay-openers below. Next to each type, I’ve added the corresponding memorable ending with examples of each.

| LEAD TECHNIQUE | MEMORABLE ENDING THAT MIRRORS IT | |

| A |

Ask a Question Are cell phones preventing students from getting a quality education? |

Answer the Question Cell phones are not preventing students from getting a quality education. They might just be the key to providing it. |

| B | Bold Statement

Any school that bans the use of cell phones might as well ban the use of pencils. |

Justify It Learning to use a cell phone properly is just as important as learning to use a pencil. |

| C | Contradiction

Using cell phones in class does not distract students, it helps them learn more. |

Explain It Away Letting students access their phone’s calendar, calculator, note-taking apps and search engine teaches them to use these valuable tools. |

| D | Description

Imagine a classroom without any calculators, dictionaries, clocks, calendars, computers, or other essential tools. |

Describe a Better Scene Picture the extra resources schools would have if they let students use their cell phones on campus: more calculators, dictionaries, calendars and search engines—all for free. |

| E | Example

A California woman and her 15-year old are alive today, thanks to a drone that brought life vests to them after their car was caught in a flooded river. |

Related Example Remember the 15-year old rescued from a flood by a drone? Today she’s an engineering student at UCLA. She hopes to design—you guessed it—drones . |

| F | Fascinating Fact

An estimated 7-million drones now take to the skies around the world, 2 million in the United States alone. |

Related Fact You know those 7-million drones flying worldwide? For perspective, consider this: there are just 30-thousand or so airplanes. That means drones now outnumber airplanes 233 to one. |

| Q | Quote

“Once you have tasted flight, you will forever walk the earth with your eyes turned skyward.” Though Leonardo da Vinci never got to fly, he certainly understood its potential. |

Related Quote While da Vinci never took flight himself, he did further its principles. He would have delighted in today’s resulting drone technology, for he also said, “Poor is the pupil who does not surpass his master.” And drones have certainly surpassed even da Vinci’s brilliant imagination. |

Word Play

Word Play

Another way to WOW readers at the end of an essay is to employ word play. Frankly, I have always limited this lesson to more advanced writers, because it is only effective when skillfully executed. Word play entails using figurative language, puns, or even sound devices to end writing with a playful—and memorable—punch. Here are a few examples.

|

Idiom Who knows where the future of this technology will lead? The drone industry is just getting off the ground. |

|

Metaphor Unmanned aerial vehicles truly are modern man’s worker bee. |

|

Simile Drones are revolutionizing surveillance and monitoring the same way wireless technology revolutionized communication. |

|

Multiple Meanings (Pun) I will leave you with that final thought on the future of unmanned aerial vehicles. I wouldn’t want to drone on about it. |

|

Alliteration Simply put, drones represent the future of flight. |

In a previous post I described how one student’s memorable ending changed the way I taught conclusion writing. Her clever “Chew on that!” ending to an argumentative essay on allowing gum in school opened my eyes to middle school writers’ true aptitude. The instructional changes I made unlocked potential that was always there, and my students’ writing scores on state assessments soared. Not only that, their ability to communicate their ideas effectively and memorably will serve them well in the future. And THAT is everything.

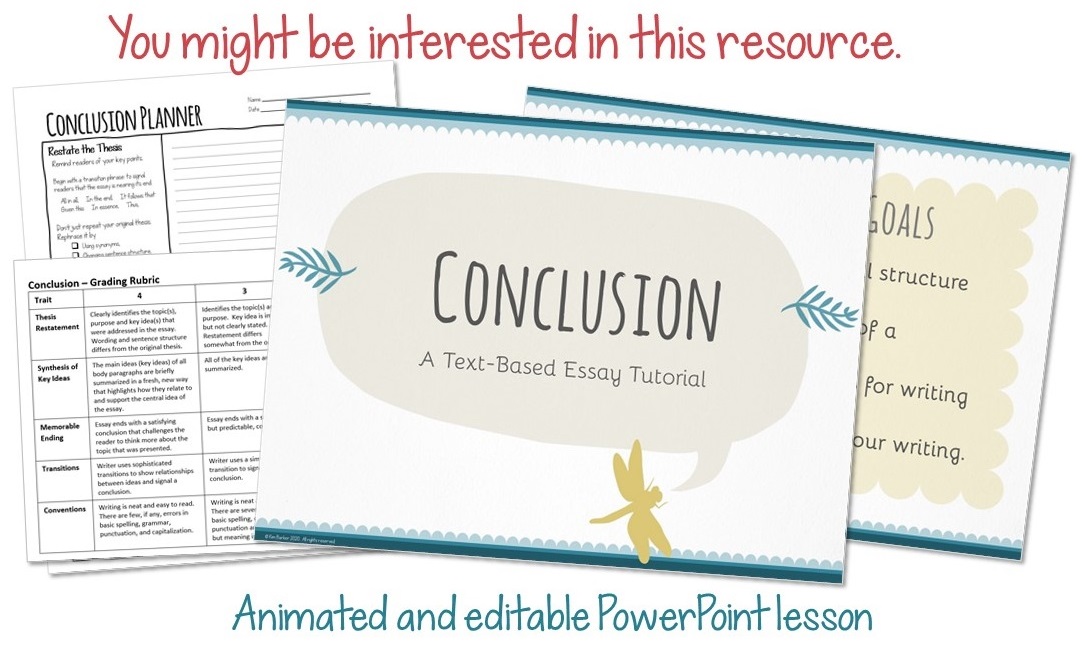

Now, if I’m being honest, I do ask students to summarize their key points when drafting the conclusion, but only as a jumping off point. In fact, I ask them to write these summaries without rereading their body paragraphs. This often yields a fresh way to convey each key point—or at least identifies the absence of a single cohesive line of thought.

Now, if I’m being honest, I do ask students to summarize their key points when drafting the conclusion, but only as a jumping off point. In fact, I ask them to write these summaries without rereading their body paragraphs. This often yields a fresh way to convey each key point—or at least identifies the absence of a single cohesive line of thought. If students identify a connection between two of the ideas—in this example they noted #1 and #3 both require self-sacrifice—ask them if that trait might also be true of #2. This often leads to deeper insight into their topic as they recognize previously unseen relationships. In this case, the student noted that justice, too, requires self-sacrifice since it requires the individual to give up personal freedoms for the good of the community at large. Once such a commonality is identified, have students explain the link and note its significance. The result is a sentence that synthesizes the ideas, and one worthy of their conclusion.

If students identify a connection between two of the ideas—in this example they noted #1 and #3 both require self-sacrifice—ask them if that trait might also be true of #2. This often leads to deeper insight into their topic as they recognize previously unseen relationships. In this case, the student noted that justice, too, requires self-sacrifice since it requires the individual to give up personal freedoms for the good of the community at large. Once such a commonality is identified, have students explain the link and note its significance. The result is a sentence that synthesizes the ideas, and one worthy of their conclusion.

#1 Use synonyms for key words

#1 Use synonyms for key words #2 Change the sentence structure.

#2 Change the sentence structure. #3 Be more expressive.

#3 Be more expressive.

The essay in question was an argument for allowing gum in schools. It was engaging, used sound arguments and spot-on evidence. The conclusion recapped key points and wove them into a convincing body of reason. But it was the final line—just three creatively conceived and artfully applied words—that rocked my teaching world. It ended “Chew on that!”

The essay in question was an argument for allowing gum in schools. It was engaging, used sound arguments and spot-on evidence. The conclusion recapped key points and wove them into a convincing body of reason. But it was the final line—just three creatively conceived and artfully applied words—that rocked my teaching world. It ended “Chew on that!”

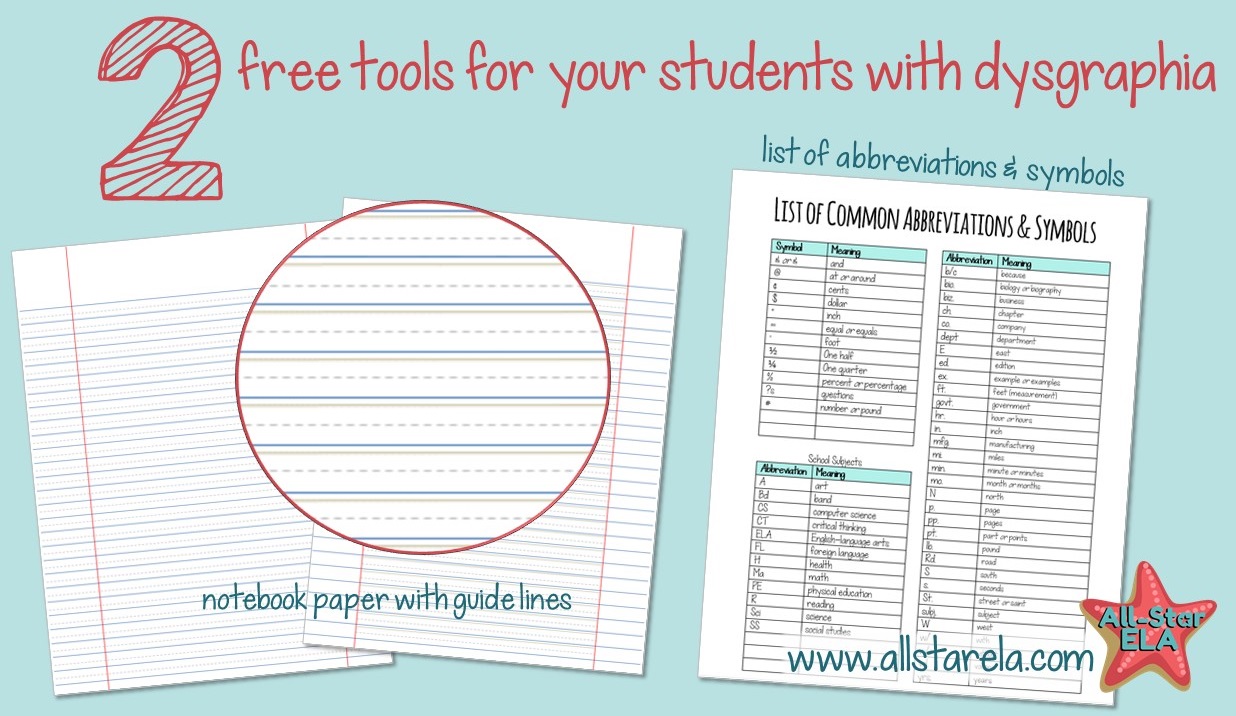

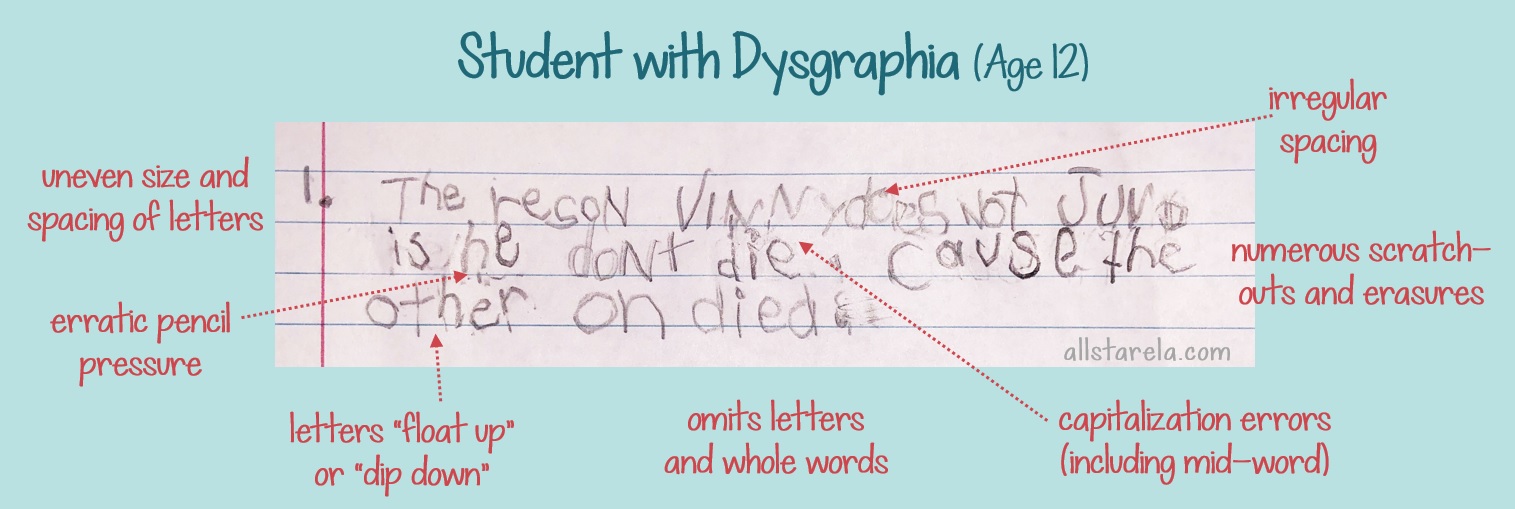

Students with dysgraphia may hold their pen or pencil in a tight or claw-like grip. They may hunch over their paper or turn their hand (or paper) at an odd angle to write. These students often avoid writing assignments and write much more slowly than their peers. Also, because so much mental energy is dedicated to task of production, it’s hard for students with dysgraphia to compose their thoughts while writing.

Students with dysgraphia may hold their pen or pencil in a tight or claw-like grip. They may hunch over their paper or turn their hand (or paper) at an odd angle to write. These students often avoid writing assignments and write much more slowly than their peers. Also, because so much mental energy is dedicated to task of production, it’s hard for students with dysgraphia to compose their thoughts while writing.